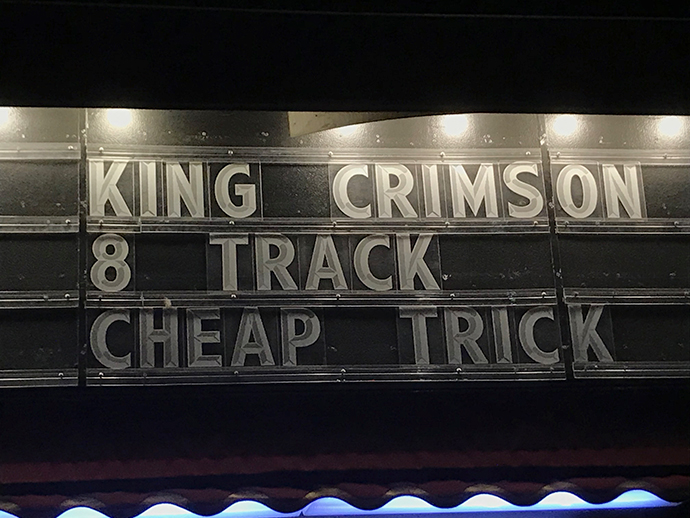

The archetypal progressive-rock band King Crimson has been sweeping through North America once again with an epic tour and expansive lineup that even pushes its own edgy frontiers with four drummers at the forefront (well, more like three drummers and a programmer, but still, awe striking), and I caught them for the second time on this tour at The Capitol Theater in Port Chester. To say Crimson is the royalty of prog rock is redundant as they were the very first to receive that label, starting off the genre way back in 1969; although anyone hearing them anytime in the last 20 to 30 years you’d find it hard to believe that this is such a dinosaur of a band, as their music continues to push, and sometimes even shove, the boundaries of serious musical experimentation to this very day. The name King Crimson is known to many a music lovers, and is often a name that is brought up when discussing extremely talented musicianship or extremely complex rock, but outside of the serious Crimson fan, many of those have at best only a passing idea of what they sound like. Many casual rock lovers are probably thrown off by the insanely complex musical structures, while more are probably confused by the copious personnel and frontman changes the group has experienced over the years. Truth be told, the only founding member of the group still present is guitarist Robert Fripp, the guy who started it all off nearly 50 years ago. He was never the frontman, lyricist, nor usually even the main songwriter, and sometimes not even the lead guitarist, but he has always been the main conductor of the project, corralling the evolution of the experiment through the decades and forever keeping this band on the experimental music fringe and the forefront the radical avant-garde.

What set Crimson apart from other preceding groups with progressive rock tendencies, like Procol Harum, Pink Floyd, The Pretty Things, and even selected post-’65 Beatles tracks, was Fripp’s insistence on stripping all blues and R&B from their music, and instead, basing the song structure on the strict framework of classical/orchestral and the wild anarchy of improv jazz, and what more, how the two genres could switch roles; with classical being the unpredictable and unhindered creature, while jazz could be the structured and organized nobility. Along with some very heady concepts about war and peace, the evolution of technology and the devolution of art, they incessantly explored both physical and abstract contradictions and contrasts in musical arrangements that continue to define the band to this very day. Still, shortly after releasing their first (and still most recognizable) album, In The Court of The Crimson King, the rest of the band left en masse to pursue very Crimson-esque efforts of their own, like founding bassist and frontman Greg Lake, who formed his over-the-top, show-off version called ELP (Emerson, Lake, and Palmer) which ended up becoming one of the most commercially successful art rock groups of the 70’s. Nonetheless, Fripp soldiered on and produced many new lineups in the early 70’s, each one with their own flavor and direction, from the rather jazzy, to the more classical, and even to the loudly bombastic rock-out edge. Still, nothing seemed to ever fully click until late 1972, when Fripp came back like a Phoenix from the ashes, first as a solo artist, creating the very first ambient music with pioneering synth artist Brian Eno, and then taking King Crimson to its edgiest era yet. With associates like a hard rock bassist and vocalist John Wetton, violinists, performing artist percussionists, and even a fellow jazz hard-liner and founding Yes drummer Bill Bruford, they produced what many consider to be the bible of progressive possibilities called Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, an album that drew deep contrasts with much of the rest of the progressive scene, even bands like Yes and Genesis that initially used Crimson as a direct blueprint, but came into huge success with ego-driven, solo-crazed, Spinal Tap cheesiness, and a show-off over substance approach to the prog ideal. The band continued to get even edgier, especially on stage, where their highly improvisational performances drew out a largely new and even more devoted cult fandom in droves. Still, just before releasing what was arguably their best album yet, the dark and edgy Red in 1974, which by then was a stripped-down Fripp, Wetton, Bruford power trio, Robert shocked fans and the rest of the band alike by suddenly calling an end to the band. Despite having just turned out some of the best work of his career, he claimed he had a change of religion, or more exactly, he just wasn’t feeling the whole progressive rock thing anymore, and needed to go in search of a new sound.

While Wetton went on to groups like Uriah Heep, Roxy Music, U.K., and the 80’s supergroup Asia, and Bruford went on to short stints with Genesis, National Health, and his own jazz-fusion band Bruford, Robert Fripp did indeed go on an epic sound pilgrimage through the rest of the 70’s, even changing his base of operations from London to NYC. Sure, he did eventually appear with many of the local emerging artists like Talking Heads and Blondie, but his major evolution was, surprisingly enough, as a session guitarist for a couple British ex-art rock frontmen who were also looking for a new sound, including Peter Gabriel through his first three self-titled solo albums, and David Bowie during his infamous Berlin sessions of “Heroes” fame. By the time he got to the 80’s, he had indeed found his “new sound,” with twisting and winding guitar rhythms and sweeping synth-addled soundscapes, and mixing more extremes like new wave and Indian music. In ‘81 he regrouped with his old Crimson-mate Bill Bruford, and they ended up forming one of the most excitingly original creations of either of their careers with bassist Tony Levin, who had played with everyone from Alice Cooper to Paul Simon in the 70’s, but his most influential work was with Peter Gabriel, with whom he perfected the use of a guitar/bass hybrid instrument called the Chapman Stick, and first time lead and rhythm guitar virtuoso, lyricist, and vocalist Adrian Belew, who started out blasting the strangest axe noises imaginable for Frank Zappa during his Sheik Yerbouti period, learned the swagger with David Bowie during his Lodger era, and spent a few years as Talking Heads lead guitarist, playing a particularly strong role on the classic album Remain In Light. At this point, Belew was already going solo, but he agreed to join Fripp’s group only as long as he didn’t have to sing and old songs and had time to do his own solo stuff in-between albums. Before they released their first album, Fripp agreed to switch the band’s name from the very apt Discipline to King Crismon, a risky decision not only because they never played “classics,” but also because they sounded so little like any previous KC incarnations. Their first album Discipline became known as one of the best experimental works of the whole decade (especially for radical guitar experimentation), and they continued push the experimental edginess over their next two albums and tours, even venturing into pioneering industrial music sonics well before their time, although the juxtaposition of Belew’s growing ability to write catchy pop songs could sometime make for a rather uncomfortable relationship. By 1984, Fripp once again threw his arms in the air in frustration, and called an end to Crimson and called for a radical shift in his own career.

Over the next decade, they all explored the ups and downs of commercial success and the more fulfilling ideals of personal exploration and experiment. Belew started off very radical, but by the end of the 80’s was doing some rather straightforward and simplistic homemade pop-rock albums, yet was still named Best Experimental Guitarist 5 years in a row, although much of that was likely for his work with other artists like on NIN on Reznor’s breakthrough Downward Spiral. Tony Levin went back to bass-playing for everyone in the industry it seems, from Bryan Ferry to a reunited Pink Floyd, but his best work continued to be with Peter Gabriel, who hit big time commercial success in the latter 80’s, and with whom Levin really broke out into all sorts of wildly unique bass augments and even began to explore his own solo career. Bruford gave up on the rock world of the 80’s altogether and ended up taking his now all electronic drum sound to his new age fusion group called Earthworks, which once again was a surprise hit, but by the end of the 90’s he made the odd decision to re-team with some of his ex-Yes pals in a project of which he was obviously the only one to still push for progressive ideals, and when they expanded into an 8-man overblown ego-fest stuck in nostalgia malaise, he joyfully went back to all-acoustic jazz drumming. Fripp, also gave up on the industry, but never one to do this half-way, he really disappeared for several years, aptly becoming a music professor, and largely only appearing on recordings he made with his students. When he entered the 90’s he suddenly became the grandfather hero idol of many new genres like ambient, industrial, and modern prog, and appeared with many from the Orb to Future Sounds of London, setup his own music label, and, of course, began concocting a whole new wild Crimson formation. His first attempt with ex-Japan frontman David Sylvian ended up just becoming a duo project, but was where he began jamming with Belew again, and sure enough Bruford and Levin also followed, and finally gave him the ability to form an idea he had been formulating called a “double trio,” which included another bass-hybrid player Trey Gunn and experimental drummer Pat Mastelotto (both of whom where in his Sylvian + Fripp group). The new six-member KC produced some of the most vibrant and electrifying work of their entire career, like the 1994’s EP VROOM VROOM, and one of my favorite Crimson albums of all time THRAK in 1995. Despite having pulled out a true creative masterpiece and a tour which was the first time I experienced them live, it turned out harder and more expensive to get all 6 of them together at the same time than you’d expect, and Fripp ended up spending the late 90’s doing a series of “single trios,” the first of which saw him and Bruford get in a fight and the latter left the Crimson in a huff, never to return to the fold again.

After the turn of the century, King Crimson was back in explosive form, returning to a more predictable Fripp, Belew, Mastelotto, & Gunn quartet formation, but that was just about the only thing that was expectable about 2000’s Construkction Of Light, which was so relentlessly hard-rocking and agressive that there was nary even a mellow interlude found anywhere on the entire LP. Their following tour saw them play along-side Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones, modern metal prog giant Tool, and even playing around with the pranksters of Primus, but their next LP in 2003 failed to live up to their energy potential and even felt a little tired. It seems as though Fripp may have been getting a bit bored of the Crimson direction, and as they all went on to solo endeavors, Fripp seems to have been attempting to craft a brand-new Crimson formation behind the seams, involving new and old members, and one that could in particular play some of their old vocal classics which Belew had steadfastly refused to do for over the last 3 decades. Still, nothing seemed to pan out, and Fripp appeared so frustrated that he all but refused to even discuss any future KC prospects. It was only after Belew implored him to do something in 2007 for the 50th anniversary of the band that he agreed in the most absolutely begrudgingly of ways possible. In a ridiculously short tour of only a few cities, Fripp was going to only be a backdrop to the shows, literally hiding behind a bank on synths as he performed with Belew, Mastelotto, and the returning Levin on bass, but he did decide to spice things up a bit at the last minute by adding a second drummer Gavin Harrison of the 90’s prog band Porcupine Tree. Fripp was obviously unfamiliar with going out with no new material to support or experimental direction to go, and the shows showed it, as they were expectedly very stripped-down affairs with almost none of their usual improvisational instrumental works peppered throughout. The only real kick in the ass proved to be the extremely potent Mastelotto /Harrison combo, and their resounding experimental play apparently even caught Fripp’s fickle ear enough to reach out to Belew to set up more tour dates, to which Belew had to decline due to previous solo commitments, which apparently enraged Fripp so much, he threw his arms up and declared Crimson dead once again.

Fripp did continue with solo work and even finished and released one of his attempted mid-00’s Crimson reformations as “A King Crimson ProjeKct” in 2011, but then got exceedingly angry at Universal Group for mishandling his catalogue, most notably when they let Kanye West sample the Crimson classic “21st Century Schizoid Man” in his single “Power” without so much as even asking Fripp himself. He ended up losing all faith in the music industry and retired from it altogether in 2012. Shortly after, much of the rest of the band started up a “battle of the trios” touring project called 2 of a Perfect Trio, in which Levin and Mastelotto’s Stickmen and the Adrian Belew Power Trio would both do sets then all six would meet onstage for an all-Crimson set, and it all proved to be a huge success. However, Fripp’s retirement lasted less than a year, and by 2012 he came back in yet another Phoenix-like moment, and immediately re-instated a new formation of Crimson. Sure enough, it was both old and new members, and most notably, no Adrian Belew, which meant they could finally have free range to play the whole KC catalogue at will. The whole last rhythm section of Levin, Mastelotto, and Harrison was still present, joined by a third drummer Bill Rieflin, who was best known as THE industrial drummer of the 90’s, playing with bands from Ministry to NIN, as well as some mellower acts starting in the late 90’s like REM and Robyn Hitchcock, and some highly experimental stuff in the 00’s. There was a face from the distant KC past, with saxophonist, and multi-instrumentalist Mel Collins, who was a member of the band from 1970-72. Then there was singer and guitarist Jakko Jakszyk, who has done several acclaimed solo albums and been part of many groups from The Lodge to Level 42, and was also frontman/guitarist of an early 2000’s touring group of ex-Crimson members called 21st Century Schizoid Band, which certainly proved he had the chops to play their “classic” material. Rieflin had to drop out of the group for a family health emergency after their debut North American tour, being replaced by Jeremy Stacey of many a 90’s staple alternative bands like The Lemon Trees, The Waterboys, Echo & the Bunnymen, Aztec Camera, and Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds. However, Rieflin did briefly rejoin the band on the next leg of touring keyboards and drum programming, then making the band an octet, only to once agin bowing out for this North American tour, this time replaced by jazz player and frequent Fripp collaborator Chris Gibson.

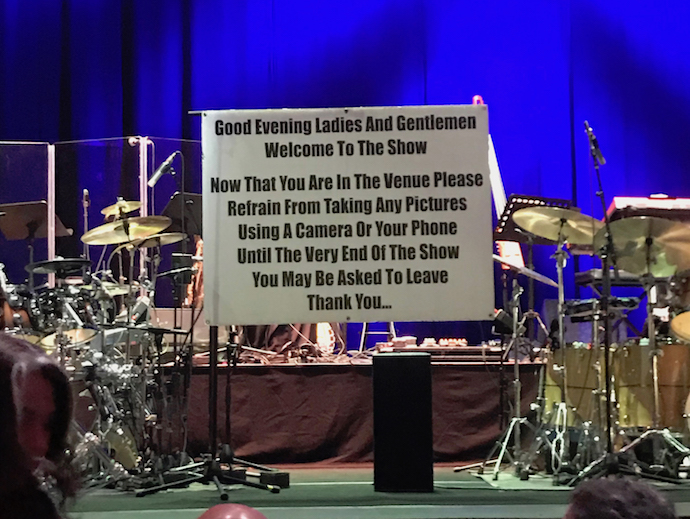

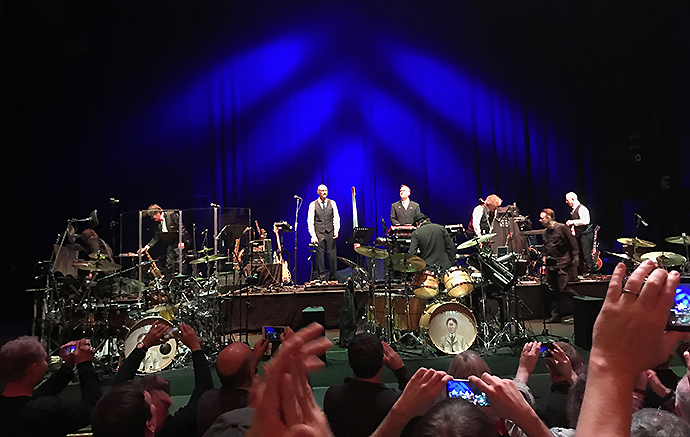

As any true Crimson fan knows, Robert Fripp is a real fanatic stickler for enforcing a “no photos policy” during his shows, encouraging people to live in the moment and not behind a screen, so even though I was given a sublime press seat up front and dead center I didn’t have to take pics, which was actually a total relief, and allowed me to just sit back and really take it all in. With the three drummers positioned up front, the focus of the shows was very clearly drums and rhythms. With just about any band, I would consider 3 (let alone 4) drummers excessive and superfluous, but I feel only a band like King Crimson that so immensely obsessed with the art of complex combinations of time changes, and packing the actual talent and expertise to pull it off, could really do it justice. Sure enough, Mastelotto, Harrison, and Stacey totally reinvented every song they touched and explored every musical technique imaginable, and some very unbelievable ones as well. Sure enough, they did play a lot of their earlier material, including more than half of their first album with “Epitaph,” “Moonchild,” “The Court of the Crimson King,” and, of course, a finale of “21st Century Schizoid Man” all mesmerizing old-timer fans starving to hear their favorites after so long. I did like that even though Jakko had the perfect chops to emulate those early singers, they never served anything up as nostalgic lip service, and always found ways to play around with compositions of even their better-known stuff to make everything a wholly new exploration. They also played a huge amount of early 70’s stuff, including material from albums number 2 through 4, much of which had never been played on stage before, but the set was definitely heavy on the fan-fave Larks’ through Red period. They did play some Belew-era stuff as well, even ending the first set with “Indiscipline” and starting the next with “Discipline.” However, they did strip out his vocals for those songs as they had on their previous tour, which I found to be a rather obvious stab at Belew’s long-time moratorium on most of their previous work.

Apparently, just recently, Fripp and Belew have finally made up and buried the hatchet, even suggesting that Adrian may re-join the fold in the future, which is insane to think they may then have 3 guitarists, two frontmen, and 9 members. Nonetheless, the only era left out during the show seemed to be their brief but fruitful 90’s works, but there was a lot of impressive new stuff peppered throughout the evening, including some very fresh-sounding improv instrumentals. Mel Collins’ sax played well to some old stuff, but also squealed nicely to cover some of Belew’s more extreme guitar bits. They even started the encore off with “Heroes,” a cover from the recently dearly departed David Bowie’s, who’s soaring guitar backing was originally performed by Fripp himself way back in 1977. It was a true delight to both spend the evening basking in nostalgia and sentimentality while also baptizing myself in brilliant innovation and originality. Then again, it is exactly that kind of mind-blowing dichotomy that has continually drawn many of us like moths to the flame back to the regal brilliance of King Crimson time and time again.

Article: Dean Keim

Photos: Dean Keim, Tony Levin, & David Singleton